Undervalued and frustrated: the hidden challenges of unpaid carers

In this special investigation for Carers Week, Mia Mohamed Sueres and Lois Barnett shed light on the lives of local carers.

At least one in 11 people in the UK is an unpaid carer. Across the country, millions support loved ones — unpaid, often unseen, and increasingly overwhelmed.

Published to coincide with Carers Week 2025 — an annual campaign dedicated to raising awareness about caring — this multimedia feature follows the lives of four carers. Through photos, video diaries, and interviews, they offer a candid glimpse into the realities of caring: a role that demands everything and often gives little back. This year's Carers Week theme, “Caring About Equality,” shines a light on the deep inequalities carers face — including a greater risk of poverty, isolation, and poor mental and physical health. Too often, people miss out on education, work, or personal opportunities because of their caring role.

A growing crisis is coming into focus. Unpaid carers — disproportionately women and those in low-income households — form the invisible backbone of our health and social care system, yet they are chronically undervalued and under-supported.

The 2021 Census revealed that more than 5.8 million people in the UK provide unpaid care. This story looks beyond the numbers — into daily lives, systemic challenges, and why carers’ voices must be heard now more than ever.

Colette

"I live day to day. Its not practical putting everything on hold. You don't get the help you need."

Colette cares for her 95-year-old uncle, who was a Franciscan friar for over 70 years.

A former chef and art student, Colette has always had a passion for creating something out of nothing—whether in the kitchen or with a paintbrush in hand.

But life changed dramatically when her father died of cancer when she was just 13. His best friend—a Catholic priest who would later become the uncle she now supports—became a steady and loving presence.

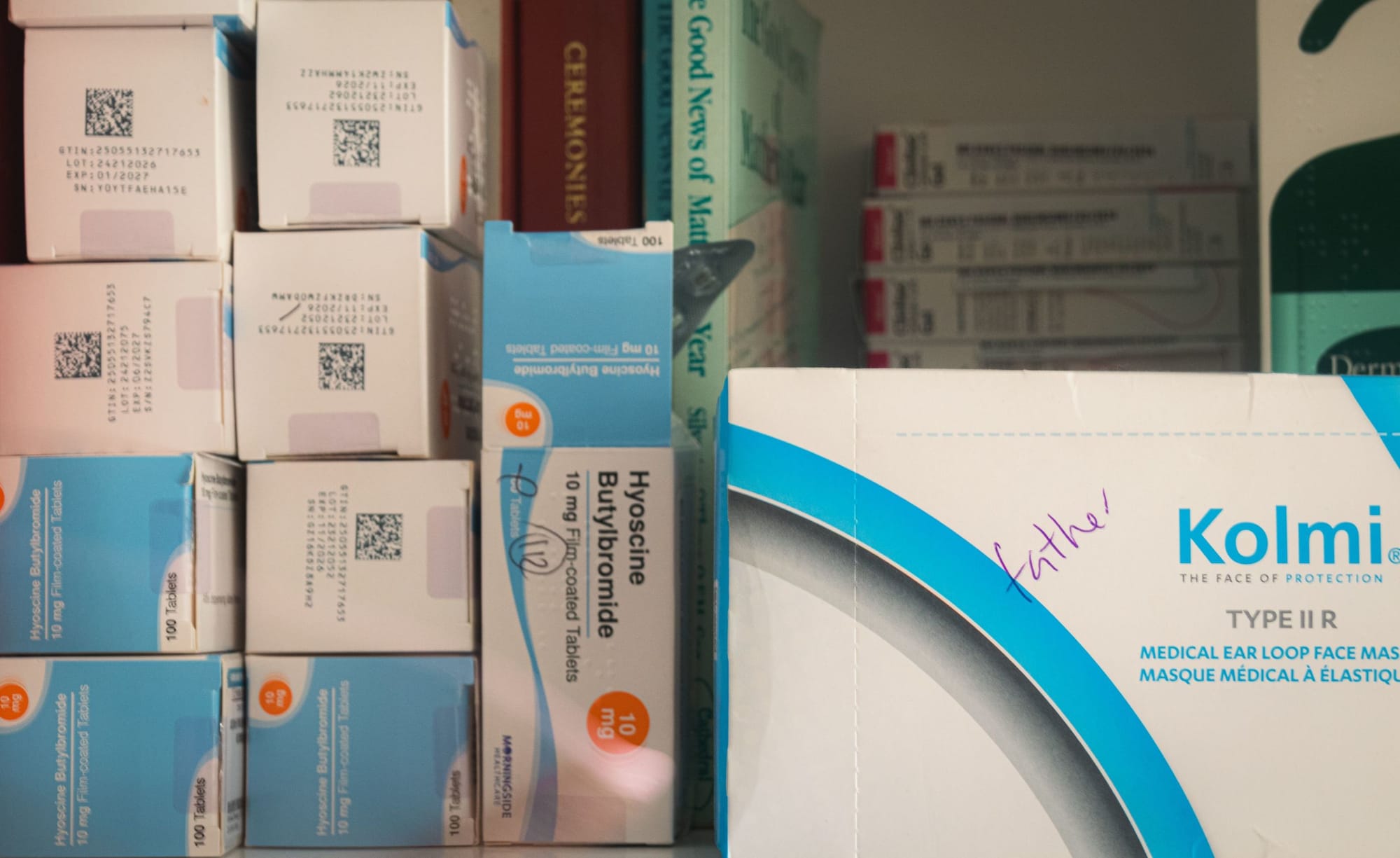

Colette began caring for her uncle in 2020. Not long after, the pandemic struck, and within six months, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, prostate cancer, and near-heart failure. The effects of COVID-19 are still deeply felt—her uncle is now housebound and refuses to leave the house. “He won’t go anywhere now and is scared because of COVID-19,” Colette says.

As his health continues to decline, Colette’s well-being is also deteriorating. The physical and emotional toll of being a full-time carer is immense. “I’m at breaking point,” she admits. “I can’t say at any given time what’s going to happen to me.”

Colette began caring for her uncle in 2020. Not long after, the pandemic struck, and within six months, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, prostate cancer, and near-heart failure. The effects of COVID-19 are still deeply felt—her uncle is now housebound and refuses to leave the house. “He won’t go anywhere now and is scared because of COVID-19,” Colette says.

“I’m at breaking point ... I can’t say at any given time what’s going to happen to me.”

As his health continues to decline, Colette’s well-being is also deteriorating. The physical and emotional toll of being a full-time carer is immense. “I’m at breaking point,” she admits. “I can’t say at any given time what’s going to happen to me.”

Support is minimal. Colette receives five hours of care twice a week, which only gives her enough time to do the weekly food shop, far from the rest she needs. While charities like MyTime offer occasional days or nights out for carers, it’s hard to make them work around her responsibilities. “I can’t get time off,” she says.

Financially, the strain is constant. The combination of PIP, Carer’s Allowance, and Universal Credit barely stretches far enough. “It’s hard to keep my head above water.” She’s also frustrated by the lack of coordination between government departments. “Someone comes out to help, and then they disappear—you can’t get hold of anyone.”

Every day starts with confusion. “He wakes up not knowing who he is. He remembers my name, but not where he is or what year it is. Then the questions start all over again.”

Karen

"Who cares for the carers?"

Karen cares for her 81-year-old mother and has been doing so since her hospitalisation eight months ago.

Karen, 62, is a retired civil servant with a busy, socially engaged life. She volunteers in her spare time and supports her 87-year-old husband, John, as well as caring for her mother.

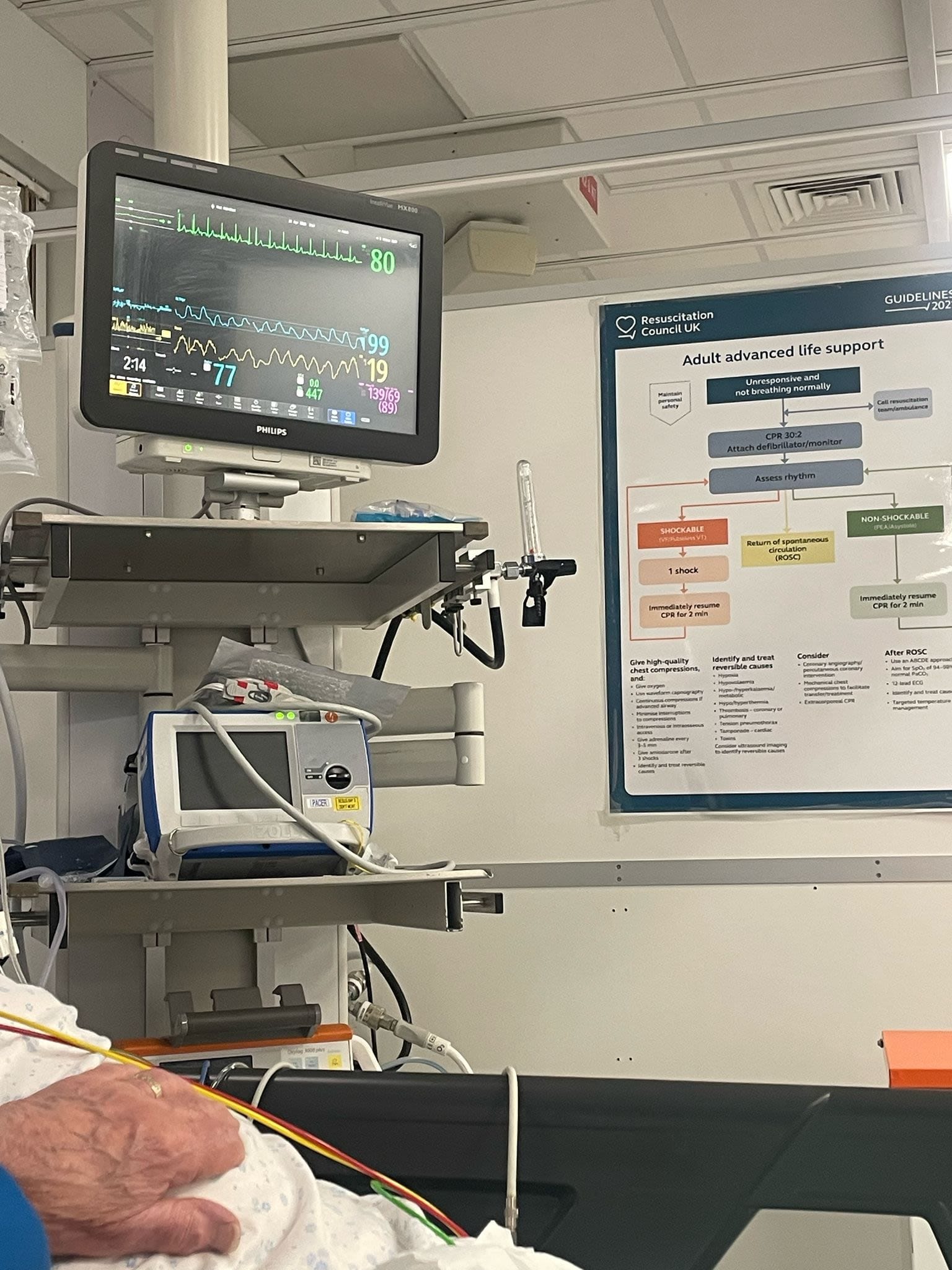

In October 2024, her mother contracted viral encephalitis. Since then, she has been in and out of hospital, spending over eight months in care. A brief six-week period at home marked the beginning of Karen’s new role as a carer - one she embraced with quiet dedication. But caring, comes at a cost.

Karen's video diary

Watch an edited series of diary entries Karen filmed over a 3-week period. It was a time of crisis—her mother was hospitalised, and shortly after, so was Karen herself, after the pressure became too much. It's a raw account of the physical and emotional toll caregiving can take - and the complexity of health and care systems that unpaid carers are often left to manage alone.

“Being a carer isn't a part-time role—it's a 24/7 responsibility, and you never truly switch off.”

Karen quickly found herself fully immersed in the responsibilities of caregiving — navigating a complex web of systems, trying to understand who is involved, who holds responsibility, and who is ultimately accountable. The experience has been overwhelming, confusing, and, at times, deeply isolating.

Karen’s role as a carer began over eight months ago, when her mother was first hospitalised. Her husband, John, 87, has also struggled to process everything that’s been happening, so Karen took the reins.

Since then, the demands haven’t stopped. From managing medication and care routines to juggling appointments, tests, and meetings with doctors, carers, and personal assistants, the list is endless.

For Karen, the most important person is her mum, who now requires 24-hour care. “Is she clean? Has her pad been changed? Is her bedding fresh? What has she eaten today?” The questions run through Karen’s mind in an endless loop, a mental checklist she carries with her at all times.

With her mum recently discharged and a full care package in place, Karen is navigating a new and complex system. This "army" of caregivers includes Occupational Therapists, District Nurses, GPs, and various specialists. However, Karen finds that communication among them is severely lacking, leaving her to bridge the gap. She recounts, "One day I made 30 calls just to try and sort out basic issues, spending up to 50 minutes on hold each time."

Amidst this, her mum has relapsed and experienced seizures, prompting Karen to call multiple ambulances. Karen feels she is always on call; it has become common for her to sleep with her phone under her pillow. She describes living in a "constant state of anxiety, not knowing what is coming next," emphasising, "She can't speak for herself; I am her voice."

She recounts being recently discharged from the hospital herself after a few days of illness, with stress being a major factor. However, back home, she feels nothing has changed. As soon as she regains her strength, it's "back to fighting again, boxing gloves on."

Help us to write more authentic content like this one with a donation to the Howfen Journal.

Angie

"I would want people to recognise being a carer is much more than a full time job, it is a way of life, you don't get time off and while you are looking after them, no one is looking after you."

Angie cares for her 17-year-old daughter, Ella, who has ADHD and severe anxiety, and depression.

Angie's life revolves around caring for her 17-year-old daughter, Ella, making each day unpredictable. "Ensuring Ella eats breakfast and is okay" is how every day begins. A significant part of her week involves a two-and-a-half-hour round trip to Ella's work, as Ella's anxiety prevents her from using public transport. Angie often cancels her plans to support Ella through difficult days, even being woken in the middle of the night. As Angie puts it, "It is quite full on and not really a predictable routine."

The journey is emotionally demanding. Though Angie finds rewards in caring, she explains seeing Ella overcome anxiety as "seeing how far she has come and that she is happy and the confidence to do it." However, it's particularly tough when Ella's depression and anxiety are so severe that Angie feels "unable to help." As Angie also manages her own mental health, when Ella's mental health dips, it often triggers her own, forcing her to manage both their struggles simultaneously.

"The hours vary depending on how she is feeling. It ranges from 7 to 12 hours a day, every day of the week."

Financial concerns are also a worry in her role as a carer. She expresses significant concern about changes to Personal Independent Payment (PIP) and Disability Living Allowance in terms of mental disabilities. If her, Ella and her younger daughter Phoebe were to lose these crucial payments, Angie fears they "will not have enough money to pay the bills or provide for them." She believes that small financial aids, such as funding a much-needed break, or respite care, would make a significant difference for carers who, as such as herself, are "just have to keep going, even when they feel ill themselves.

Ella's struggles are rooted in ADHD, with her unmet needs in high school escalating into severe anxiety and depression. The added pressure of GCSEs, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and bullying in her final two years of school exacerbated these issues. This has resulted in severe mental health difficulties that have made it impossible to continue her education at the moment, and at present prevent her from doing anything outside the house independently.

Lynne

"You don't want to admit that you can't cope."

Lynne cares for her husband Neil, who is a veteran and has been undergoing treatment for cancer.

Lynne began caring for her husband, Neil, last Christmas after he underwent immunotherapy treatment for cancer. With a background in care and caring for her previous partner, she was no stranger to the realities of the role. However, the lack of social contact, disrupted routines, and the constant mental load often leave her feeling isolated in her responsibilities as his caregiver.

“I’ve been caring for him since Boxing Day,” Lynne explains, sitting in her garden, surrounded by blooming flowers and neatly painted garden furniture. “He was in hospital for two weeks in Salford, and I was going down every day—getting a taxi.” Since then, no two days have been the same.

“If a relative has cancer and they’re your partner, usually you discuss things,” Lynne says, matter-of-factly. But Neil is different. “He’ll tell people he had a brain operation, but he won’t tell them he’s got cancer.” Lynne believes Neil hasn’t fully processed his diagnosis. “It doesn’t enter his head,” she says. She often finds herself repeating the same explanations, answering the same questions, trapped in a daily cycle she navigates alone.

For Lynne, the financial issues of care is not the biggest burden, it's the mental toll. She used to attend a craft evening in town every Monday and go to the Salvation Army for Knit and Natter, "I don't go out anymore. He won't have anyone coming in. Im stuck." Sometimes caring leaves her wondering what support can be offered, recalling an organisation saying they would put her on a buddy scheme, she admitted, "I don't know how that is going to work", or "what they want me to say."

Neil's hat and glasses, and with Lynne, hand in hand

Though Lynne isn’t entirely sure what support for her would look like, she says that simply having someone to talk to—or just to vent—would make a difference, without feeling like she’s admitting “defeat.” She doesn’t want to reach the point of saying she “can’t cope.” Some days are “good,” she says, but on others, “you climb the wall.” Thinking about caring for herself doesn’t feel like an option. Lynne feels she has to be there for Neil every moment of the day. Even during conversations, she explains, “he just looks at me, and I have to answer for him—I have to step in.”

Julie

"I put myself on the backburner. If I can't look after me I can't look after who I am caring for."

Julie cares for her partner, who has Bipolar Personality Disorder.

Julie has spent much of her life as a carer. She supported a previous partner for seven years following a brain injury, looked after her mother during a long battle with dementia, and now cares for her current partner, who lives with Bipolar Personality Disorder. Her life, she says, has been shaped by trauma, including a family history marked by suicide and chronic illness.

Reflecting on her role as her partner’s carer, Julie explains that although he is physically capable, his mental health is 'deteriorating rapidly.' She shares, 'If I weren't there, he would stay in bed all the time.' While others may not immediately see why her partner needs care, Julie emphasises that he relies on her for nearly everything. From everyday tasks that many take for granted, she notes, "He won’t answer the telephone, he doesn’t open the door, read letters, or know how to pay the bills without me."

Julie recalls that when she was caring for her mother, who had dementia, much like now with her partner, time for herself was almost nonexistent. Her only break came when friends stepped in, giving her a few hours to play darts and dominoes—brief moments of normalcy in an otherwise demanding routine. It was during this time that she realised that without looking after her wellbeing, she couldn't effectively care for others. 'Carers don’t get the same support as the people they look after,' she says. "You give up your life, your work, for someone you love. And you do it without question."

Support for Carers in Greater Manchester

Accessing support for carers is essential, and across Greater Manchester, many organisations are working to bridge the gap by offering a wide range of services. Groups such as Wigan and Leigh Carers and Bolton Carers Support provide help with benefits and financial advice, assistance with form filling, access to peer support groups and befriending services, as well as counselling and respite breaks.

An example of a targeted initiative is My Time in Wigan, which offers unpaid carer opportunities to take part in leisure, cultural and educational activites help them take a much-needed break while also enhancing their wellbeing.

If you're a carer and need support

If you’ve been affected by the experiences shared in this story, help is available. Whether you need emotional support, financial advice, or simply someone to talk to, the following organisations may be able to help:

- Carers UK – Offers expert advice, a helpline, and online support forums.

www.carersuk.org | Helpline: 0808 808 7777 (Mon–Fri, 9am–6pm) - Carers Trust – Provides local support services and grants for unpaid carers.

www.carers.org - Mind – For mental health support, including for carers managing stress or anxiety.

www.mind.org.uk | Infoline: 0300 123 3393 - The Mix – For young carers under 25 needing support.

www.themix.org.uk | Text: THEMIX to 85258 - Citizens Advice – For help navigating benefits like Carer’s Allowance, PIP, or Universal Credit.

www.citizensadvice.org.uk - Bolton Carers Support

Website: www.boltoncarers.org.uk

Email: info@boltoncarers.org.uk

Phone: 01204 363056 - Wigan and Leigh Carers Centre

Website: www.wlcccarers.com

Email: info@wlcccarers.com

Phone: 01942 705959